June 17th, 2014 After a few days at home to recharge batteries, send emails and run errands, I headed north again, crossing state lines into Umpqua National Forest. Located about 20 miles from Glide, Oregon, my next focal roost was located within a former Forest Service complex. Referred to as the Steamboat Compound, the buildings now house temporary forest fire fighters and offices for the Oregon Department of Transportation. Nestled among Douglas fir forest, there is also a small residential community in the immediate area. On my previous scouting mission, the bats had been mostly roosting in the ODOT office building. Since then, some of the bats had also expanded to roost in some of the other nearby building, squeezing themselves into the wood siding panels. Between the two roosts, I estimate that approximately 200 – 250 bats are roosting among the buildings. I decided on a spot for my bat box, away from the roost but also out of the way of the road and office buildings, and set up my equipment for the night. Then I headed over to get settled into my campsite at Canton Creek Campground, across the river and alongside Steamboat Creek.

Photo evidence of bat activity

Caught in action, emerging from the roost for nightly foraging.

June 18th, 2014 After retrieving my equipment in the morning, it appeared everything worked through the night, which I took as a good sign. After downloading my data and double-checking the files, I headed out to explore the area. I stopped at the visitor center in Glide and picked up a guide to trails in the area. Following along the North Umpqua River is a 79 mile long trail, extending from Rock Creek east all the way to the Cascades. Fittingly called the North Umpqua Trail, I decided to make it my first stop. I started at Swiftwater Trailhead, and went about four miles down what is referred to as the Swiftwater Segment. Less than a quarter mile from the trailhead, the trail looped down to a beautiful view of Deadline Falls, a spot where during the months between May and October, salmon and steelhead can be seen making their way from the ocean back to their spawning grounds. Continuing along the trail through hemlock dominated canopy and fern covered ground was Fern Creek Falls, a picturesque little waterfall. Spotted along the trail were several very excitable woodpeckers and the unmistakable Pileated Woodpecker. Despite its proximity, it was a little camera shy and I wasn’t able to get a good shot of the bird.

Deadline Falls.

Fern Creek Falls

June 19th, 2014 After yesterday’s hike I was in the mood to see more waterfalls. After a relaxing morning by Steamboat Creek, I headed out to Fall Creek Falls National Recreation Trail. I feel like “Fall Creek” has to be the most common creek name found in the United States. The mile long trail passed through some narrow boulder crevices, following alongside Fall Creek. On the way to the falls, I took a short detour along Job’s Garden Trail, which ended at the base of a large basaltic, columnar rock out-cropping, demonstrating unique geologic warping and uplifting. After admiring Fall Creek Falls, I headed back west a little farther to the Susan Creek Falls Recreation Trail, which followed along Susan Creek, ending at the dramatic falls. Dippers could be seen bathing themselves along the creek and base of the falls, as well as some teenagers indulging in a romantic picnic.

Susan Creek Falls

Fall Creek Falls

For a little more of a challenging hike, I headed to the Wright Creek Trailhead, the western starting point for the Mott Segment of the North Umpqua Trail. About 1.5 miles east of the trailhead, the McDonald Trail climbed up the ridge, passing through second growth and old growth forests. I huffed and puffed my way up the trail, passing by remnants of an old homestead before heading back down the trail. Tonight was my first night of playbacks in Oregon, and I wanted to give myself plenty of time to set up my equipment.

Part of the old MacDonald Homestead.

This little fellow gave me a little bit of a start, though maybe not as big as the start I gave him (or her).

That evening, as I was waiting for sunset, I was entertained my numerous songbirds as they did their nightly bird activities. Violet green swallows showed off their acrobatics, chirping and chasing each other through the air, sometimes flying very close to my head in their descents. A western tanager set himself up in the top of a tree, proudly displaying and singing while a female fluttered around in a nearby tree. As sunset approached and my equipment was set to record and play, I lingered, watching as bats started to join the acrobatic swallows in their nightly foraging quests. As my first study organism, swallows hold a very special place in my heart, and their cheerful chirping never fails to make me smile. If I was to write a song, a few of MY favorite things would definitely include swooping swallows and fluttering bats.

Western Tanager, singing away in his tree.

June 20th, 2014 I was dismayed this morning to discover that my DVR had once again failed to record, starting about halfway through the night. While I still had some video for the night, I had hoped my technological difficulties were behind me. I resolved to try a new battery setup for this next night, and waking up to check every couple hours to make sure things were still recording. For my daily hike, I decided to check out the Bradley Ridge Trail. The trailhead was at the end of one of the many Forest Service roads that snaked their way through the forest. The trail followed along a forest ridge, with views of the North Umpqua Canyon, gradually descending about 500 feet to the Dog Creek Indian Caves. The Umpqua Indians had inhabited much of this area and the canyon. Despite vandalism and looting, the caves still displayed ancient pictographs of hunters and random animals, as well as offering spectacular views of the rocky canyon and surrounding forests.

Dog Creek Indian Caves

Pictographs on the cave walls.

June 21st, 2014 Despite my best efforts during the night, the DVR still was having issues recording the video, though I was able to keep it going by restarting the recording process every few hours. Confused, I decided to try my original DVR setup (the one which had failed on my first night in Smith River), and to my surprise (and relief) it appeared to be working again. Feeling relieved, I headed across the highway to the Mott Bridge Trailhead, which was conveniently at the same location as both my study site and my campsite. I ran west along the trail to the McDonald trail junction before heading back, approximately an 8 mile run. It was my first run longer than an hour in over 6 months, but felt surprisingly good! Following my run, I snuck in a shower at one of the campsites and stopped in Glide for a well-deserved ice cream treat. Since my run had been longer than I was used to, I decided on an easy afternoon hike along Illahee Flat Trail. The trail started off another forest road, next to the Illahee Flat Gazebo. The gazebo was built in the 1920s as a recreational building for an early guard station. The mostly flat trail followed through old growth fir forests, the trail cluttered with giant cones, some bigger than my head! After passing through some open meadows, the trail joined with the Jessie Wright segment of the North Umpqua Trail and I headed back to the campsite. As I was making my way back down the Forest Service road to the main highway, a grey fox dashed across the road in the front of me, big grey bushy tail in full display. I quickly hopped out to try to see where it had run, but it had already disappeared in the forest.

Giant pinecone!

Tonight was my last night of playbacks, with Free-tailed echolocation calls having been randomly selected as the last playback type. I decided to try out my original DVR setup, which now appeared to be working properly, and while checking it through the night, it recorded the whole night without needing my interference. June 22nd, 2014 For my adventure today, I had planned to hike the Deception Trail, which would lead me up in the hills before meeting with the Twin Lakes Trail, part of the Twin Lakes Unroaded Recreation Area. However, as I attempted to follow the directions in my trail guide, I realized how unlikely it would be I would make it to the trailhead. Lack of road signs, nondescript mileage descriptions and ultimately a large tree across the road made it impossible to determine which road would take me to the trailhead. I spent the way back down the hill wishing I had a map of the area (and realizing how disappointed my father would be when he read that I didn’t have a map in the first place). Instead I decided to walk along the Marsters Segment of the North Umpqua Trail, starting at the Calf Trailhead. The trail took me by an old growth Douglas-fir grove, with 5 to 7 foot diameter trees estimated at over 800 years old. Part way along the trail, I also encountered a curious Stellar’s Jay fledgling, and a pair of very agitated jay parents. While the juvenile continued to beg, the adults barraged me with angry squawks until I had passed by a suitable distance.

Along the Marsters Segment of the North Umpqua Trail.

At the end of the trail segment was Weeping Rocks Spawning Beds, where Chinook salmon being and end their lives. Each fall, Chinook salmon return from the Pacific Ocean to spawn at this site, producing thousands of eggs. Only about 2% of those spawned eggs turn into adult fish and make it back to the spawning grounds. Imagine facing those kinds of odds just to survive and reproduce.

Weeping Rocks Spawning Beds

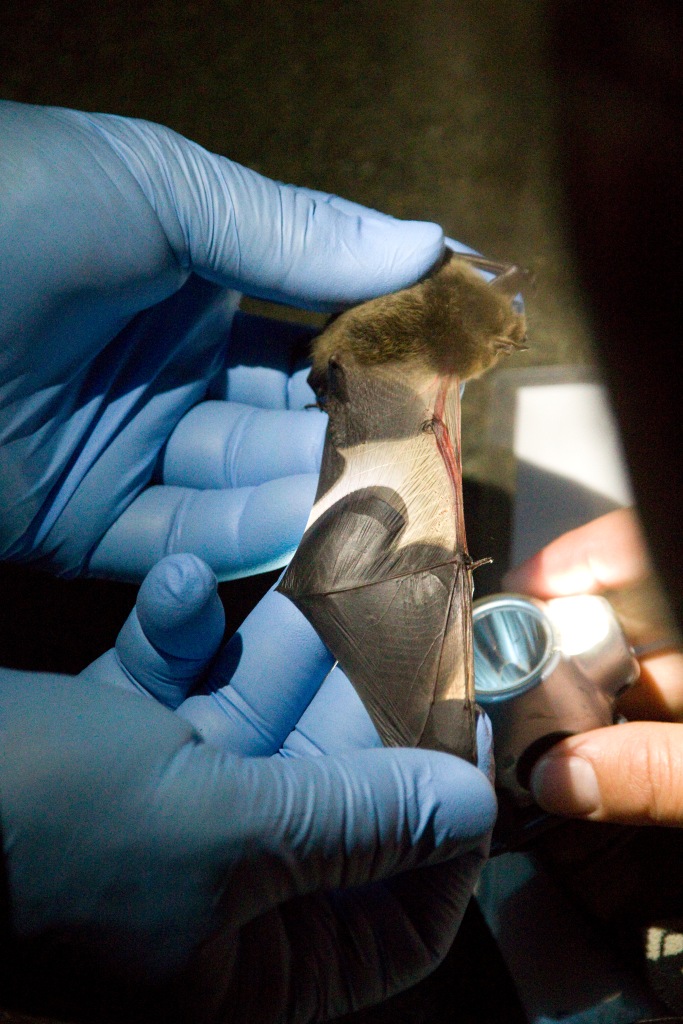

June 23rd, 2014 Last day in Umpqua National Forest. After another botched attempt at finding a trailhead, I settled for a last afternoon along Steamboat Creek. That evening, I set up most of my equipment and was hanging out at the site waiting for sunset. The swallows were going crazy above my head, chasing each other left and right. I set up my equipment once last time to monitor bat behavior after a series of playbacks and headed back to camp. Despite some issues with camera equipment, my second week of playback went much more smoothly than the first. Even with the issues, I think I have finally figured out a reliable way to get data and am hoping that this will be the last of my technological issues for the summer. After getting home and checking my email, I learned that my permit application for bat handling and capture in California had been approved. I am now officially permitted to carry out mist net surveys and the capturing and handling of bats in California!